Access all areas

Access all areas

How Facebook and former Muslims are bringing Jesus’ hope to North Africa, thanks to the workers you support.

“I’m the only Christian in my country.” BMS’ media mission is streaming the gospel into parts of the world where fewer than one percent know Christ. This is the story of the voices who reply.

There’s less than five minutes until we go live when the team rush into the studio to pray. Presenters Joe and Zinah are poised on set, microphone wires tucked into crisp shirts, the sound check finalised. ‘There’s not enough time,’ I think. ‘Praying now?’ But the media centre I’m visiting is fuelled by three things: coffee, hard graft and prayer. Back in the control room, I perch on my seat. “Don’t forget, you can pray too!” says Andrea, BMS’ Director of Arabic Productions from her seat at the switch deck. I bow my head. Five, four, three, two… one. We’re rolling.

I flew to the media centre, situated in a secret location in the Mediterranean, at the beginning of Ramadan. I’m here to experience the broadcast of a Facebook Live Stream, one of several shows that are filmed for North African audiences at this time of reflection and celebration for the Muslim world. The shows, presented by North African Christians Joe and Zinah, are aimed at encouraging questions, with the hope that discussions will point towards knowing Jesus in a Muslim context.

Tonight’s broadcast is about fasting: interrogating its purpose and how to do it well. There are no water glasses on set – the team want to be culturally sensitive especially during Ramadan. As Joe and Zinah warmly welcome viewers to the show, the first comment pings up on a Facebook thread. Habib, the centre’s Christian apologist, taps out a reply for all those watching the stream. For those who don’t want to leave a public comment, Habib opens Whatsapp. These private channels are where the most thrilling conversations happen. Truth-seekers speak more openly behind the protective walls of encrypted messaging.

We’re halfway through. Cameras on her, Zinah’s speaking so confidently, but just an hour ago she’d been close to tears. As they sat in the makeup chairs, with Andrea multitasking as foundation retoucher and translator, Joe and Zinah had been telling me about last week’s show, where Zinah had received an angry comment telling her to return to Islam live on air.

Ordinarily these comments are ignored, but Zinah had surprised us all. “I cannot leave my God of love,” she’d told the viewer. “God is not angry with me. Jesus says we have eternal life.”

“In that moment, I felt that I was really strong because Jesus was with me,” Zinah said, her eyes shining. “It was a healing from the past. From culture, from religion, from the man having more right to say things than you. From being ashamed.” I know that Zinah has been rejected by family – almost all the North Africans at the centre have been. But they bear no ill will. “When most of our families are still Muslims, how can we be against them?” Joe says.

Their commitment to grace is still evident during tonight’s show, and Ian, BMS’ Studio Manager and Producer gives the presenters the signal to wrap up. Joe and Zinah field final questions about how Christians can respect their Muslim families during the fast. Then, we pile into the prop room to hear who Habib has been speaking to.

A lady called Khadisha has been inviting her friends to watch the show. Then, a strange and disjointed message arrives over Facebook. Hani is a refugee living in Turkey who has seen the Facebook Live and wants to talk, despite the show being in a very different Arabic to his own. He’s so interested, he’s willing to struggle on in a dialect he can barely speak.

When Habib, who lost half his family in an Aleppo bomb blast, realises Hani is Syrian like him, he laughs in delight. They speak the same kind of Arabic. Hani’s been wanting to know more about Jesus for a long time, and now he’s found someone who can tell him. It’s like it was planned.

Habib tells us about Fatima, another viewer who’s overwhelmed by a dream in which she saw Jesus, and Si’id, an atheist who wants to be sent an Arabic Bible. Some viewers introduce themselves as ‘Ahmed’ or ‘Hassan’, only to reveal themselves weeks later as nervous women, hiding behind the protective power of a fake name. New believers will be connected with churches in North Africa. Over 150 others have seen the broadcast by the time we leave the studio. Only Habib will be up until midnight, conversing, reasoning and explaining.

With paid advertising the video would reach hundreds of thousands, but I’m about to find out why it’s not just a case of being willing to pay. I’m with Ian when he chuckles. One of the videos has had its advertising pulled by Facebook. It’s disheartening to know it will appear on the feeds of hundreds instead of thousands now, so the team have to laugh in moments like this. Facebook wants to be sure to avoid controversy, so some adverts are rejected – the videos must be clever, almost parabolic, in order to slip through the algorithms. “It was too religious in nature,” Andrea tells me later.

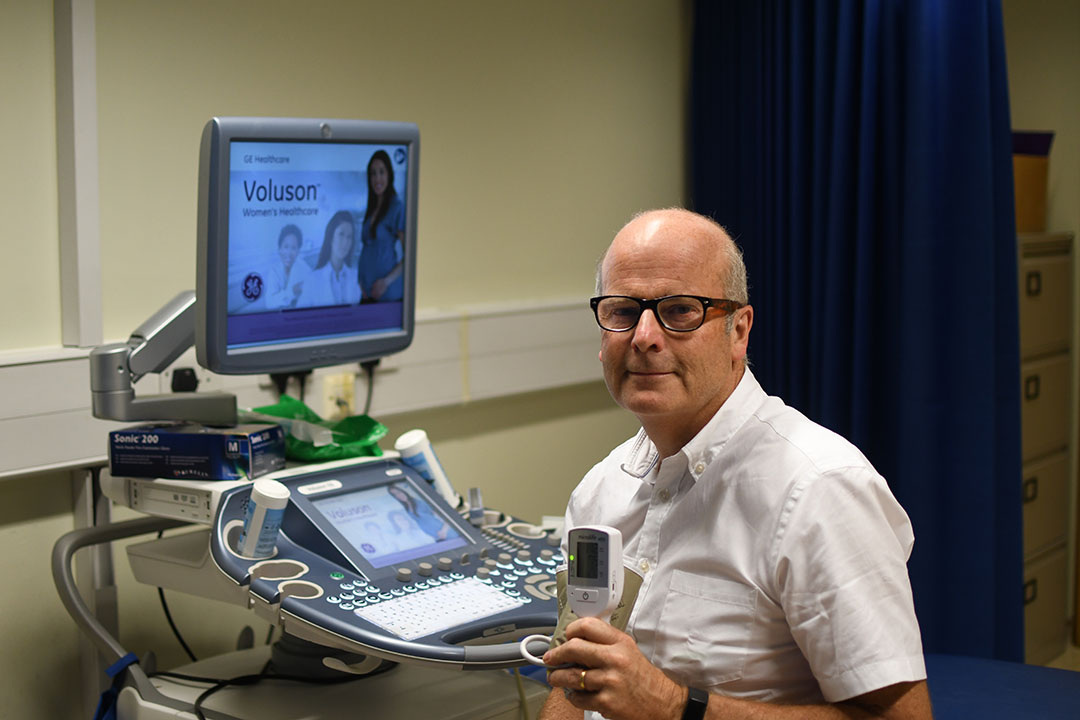

Laughing in the face of this, given all the work that’s gone into the show, is possible when you’ve been doing it for as long as Andrea and Ian have. They’ve been here 15 years, reaching out and listening to replies. Using their media skills to share hope. “They’re the grease that moves the wheels,” their team members tell me. “Heck, they’re the whole car.” Andrea laughs at this, but concedes that they are the “glue”.

Variously centre managers, directors, prop researchers, production editors and financial managers, Andrea and Ian even built the studio we’re now sitting in. When they began serving with BMS, no-one else was making Christian television programmes for North African people in their own dialect. “Now, our audience are seeing the gospel as something that can belong to them,” says Andrea. “Jesus isn’t just for one country, or for the West.” In a world where technology can often feel like a destructive influence and social media a drain, BMS workers are harnessing their power to share Jesus. And, because you support Andrea and Ian through your giving, through social media technology, Jesus is being met. “We’re on the front line,” says Andrea, “but BMS supporters are what’s helping us to stay on the frontline.” Ian agrees. “We can’t do it without your prayers.”

Pray for Andrea and Ian as they reach out to North Africa with the gospel:

- Pray that language barriers would not mean people miss out on the treasure of the gospel.

- Pray for Hani, that he will continue to grow in the knowledge and love of Jesus.

- Pray that Christians will have freedom to share the gospel in North Africa.

- Pray that God would call the people he wants to win for him, and that Andrea and Ian would be led to do God’s will in all their work.

- Pray for continued financial support for BMS, so that ministries like Andrea and Ian’s can continue.

Words by Hannah Watson, Editor of Engage, the BMS World Mission magazine.