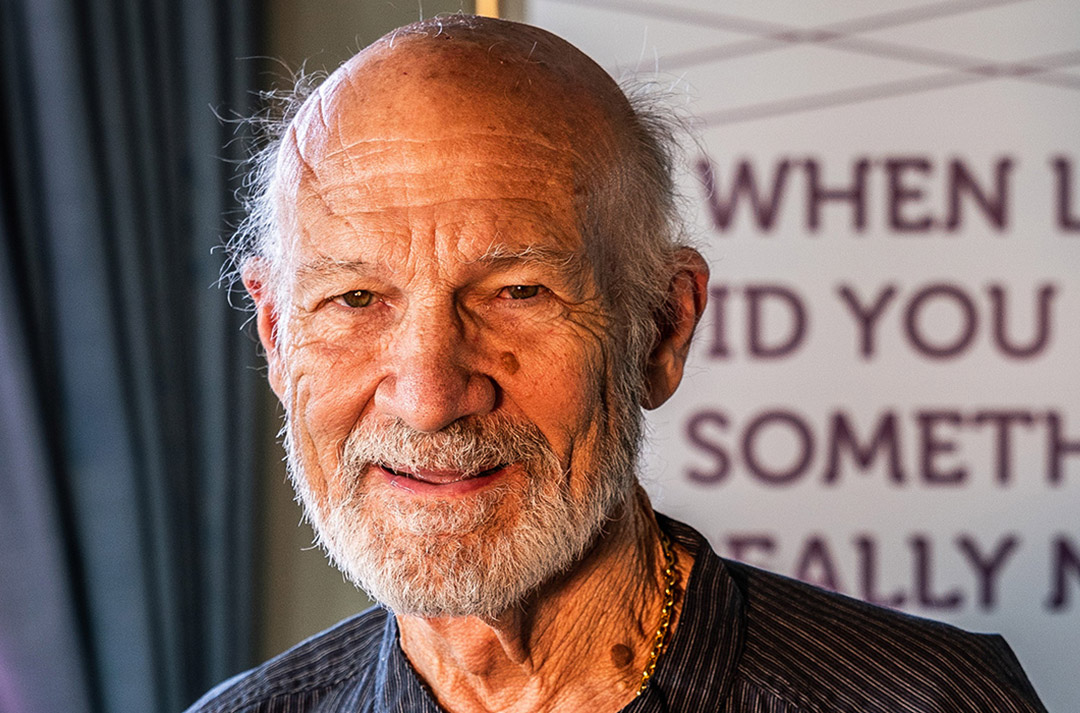

A Q&A with Monty Lyman

A Q&A with Monty Lyman

Dr Monty Lyman, author of The Remarkable Life of the Skin, spoke to Mission Catalyst magazine about life on a Covid ward earlier this year. The interview is a fascinating read! If you want to hear from more engaging Christian thinkers, why not subscribe to Mission Catalyst today?

You’ve written a book about the skin. We’ve all been told that we need to wash our hands more because of Coronavirus, and my hands are in not a good state from all the hand sanitiser. Is our skin ever going to recover?

Thankfully, our skin is incredibly tough and resilient, and our whole top layer of skin, the epidermis, replaces itself every 30 days. So, I think even if we continue fairly regular hand washing practices, it won’t affect them in the long term. But I highly recommend moisturisers, cheap moisturisers are shown to be just as effective as the really expensive ones that you get in shops.

We’re spending billions on new treatments and vaccines for Covid-19, which is great, but actually the most powerful anti-viral for these kinds of coronaviruses is just soap and water. Essentially the individual soap particles completely destroy the outer membrane of the Coronavirus, so it’s probably the most effective weapon we’ve got.

It’s really interesting, in hospital a lot of the doctors are saying that cases of norovirus and other infectious diseases have dropped massively and it’s almost certainly because of increased hand washing.

What was it like working on the Covid wards, knowing you were at risk of catching the virus?

To begin with it was scary. It was scary when we saw that our senior consultants, including some professors who seem to know everything, had never seen this disease before. When the influx started, we were in A&E all looking at patients coming into the wards, and we were looking at CT scans of people’s chests and seeing something that we’d never seen before – damage across the whole lungs, really severe pneumonia that we’d only see rarely, and almost every patient coming in had the same thing.

It was also scary that it’s a disease that we didn’t have any treatments for. We had oxygen, but that wasn’t necessarily effective, and we just didn’t know whether a patient was going to get better or deteriorate and require ICU. Probably the hardest bit about it as well was the fact that patient’s relatives weren’t able to come into the ward at all.

But actually, on the positive side, there was a lot of camaraderie. It’s easy to moan in the NHS but, when the Coronavirus crisis kicked off, we increased our intensive care unit capacity massively, we repurposed whole wards, we got retired doctors and medical students in as incoming junior doctors – it was really impressive what we managed to do as well. So, it was equally terrifying yet exhilarating.

Monty’s whole interview was included in the latest issue of Mission Catalyst, BMS World Mission’s magazine for thinking Christians.

Subscribe today for intelligent and challenging commentary on the most important issues facing Christians today straight to your doorstep, three times a year. And it’s completely free – how could you say no?!

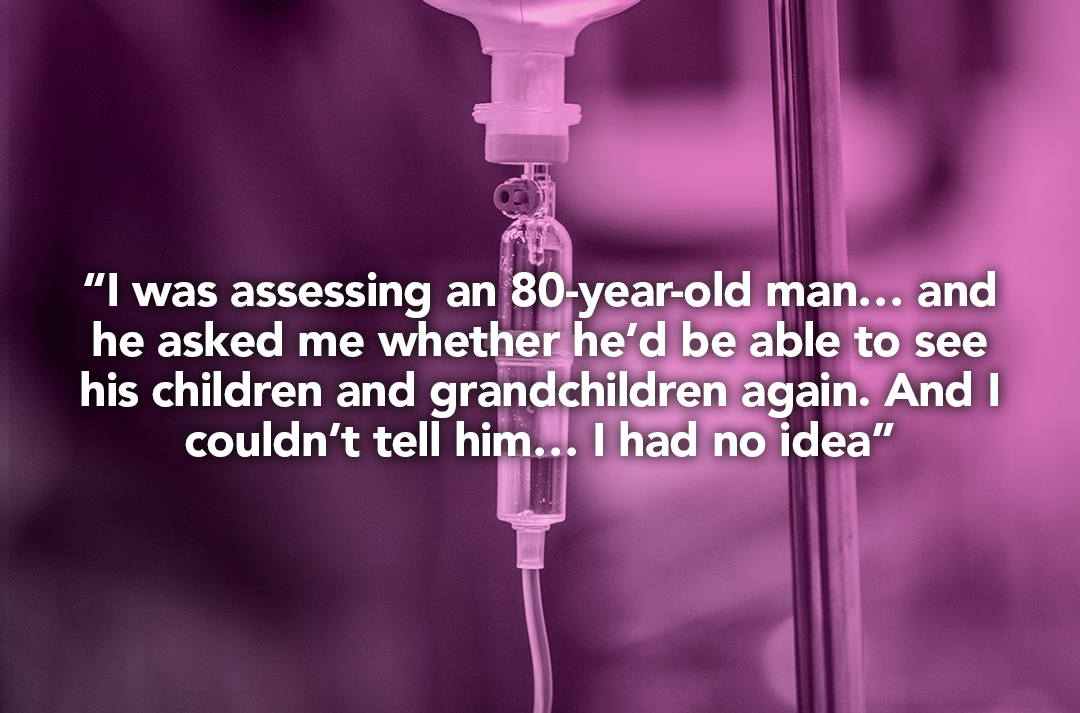

Are there images that will stay with you from having worked in that environment?

I think one of the hardest things was when I was assessing an 80-year-old man who started on oxygen on my ward and had moderate Covid symptoms. He’d just come off a Zoom call with his family and he asked me whether he’d be able to see his children and grandchildren again. And I couldn’t tell him whether he would or he wouldn’t, I had no idea. And it was humbling.

I think on a big scale, we feel in western society anyway that we’ve defeated a lot of disease, especially a lot of infectious diseases, and we’re on our way to overcoming cancer and ensuring we live long, healthy lives, but actually this disease has exposed that that’s not the case at all.

Chances are we’re going to have more pandemics in the future, what does our health system need to look like in order to continue to cope and perhaps better cope with pandemics like this?

We need a cohesive strategy with investment, cross-party. We need more long-term investment, it’s very easy for governments of all shapes and sizes to think about the short-term in terms of investing in a pandemic response. Our issue was that we just thought about influenza, we hadn’t thought about coronaviruses, even though the warning signs were there with SARS and MERS and other outbreaks of the past. So we need, with all of healthcare, to have a long-term, big picture view and we need to invest in preparing for another pandemic, because it will come.

I think this is also a big opportunity to look at inequalities in healthcare across society. People from Black and Asian minority ethnic groups and low-income groups have been more adversely affected and we need to look into the reasons, we need to have a full investigation as to why this happened and have a large public health discussion about inequalities in healthcare as well.

Within your ward and within the NHS, what did people think about the clap for carers?

It was mixed. People were positive about it, but there were also those who were saying we should have more support, and that energy should have been put more into things like PPE and investing in frontline workers. But it’s complex. Personally, I don’t have an easy answer because actually the PPE issue in our hospital was ok.

It’s been great to see public appreciation for what we’re doing because we were put at risk. I know fellow staff members who went into ICU, I know members of staff who died. I got Covid myself and was out for a couple of weeks and it’s good to see that recognised. I think maybe this could be linked in with having a more coherent plan in terms of PPE, and maybe the country needs to have a more streamlined way of stockpiling and distributing protective equipment around the country. So we do need to be better prepared for it and could have been better prepared for it. But credit to the hospital managers who managed to deal with the national PPE shortage pretty well.

Want to hear more thought-provoking Christian voices like Monty’s? Subscribe to Mission Catalyst magazine today!

Monty Lyman is a doctor and the author of The Remarkable Life of the Skin. He worked on the frontlines of the Coronavirus pandemic and is currently writing a book on pain, which will be published by Penguin in 2021.